Math Puzzles

Solving the Birthday Problem on Mars

I was recently asked to develop a challenge problem for the Metis data science bootcamp. Perhaps it was my background in math or maybe my penchant for mild torture, but I decided to have students answer a few exercises from Fifty Challenging Problems with Solutions by Mosteller. This book is full of classic problems in probability, and I highly recommend it to anyone prepping for data science interviews!

One of my favorite sections in this book is the birthday series, which includes a version of the birthday problem. This problem is about as famous as a probability question can get. It has been featured on NPR, written about in an Arthur C. Clarke novel, and it even has its own Wikipedia page.

The problem goes something along the lines of:

If you haven’t solved this one before, feel free to take a moment and give it a shot. Be warned – spoilers ahead!

Solving with Probability

Rather than the brute force approach, it turns out that the answer can be found much more easily by considering the complementary case; that is, “How many people can you invite to expect a 50% chance that all invited people have unique birthdays?” This “unsuccessful” probability along with the “successful” probability will sum to one.

Keeping the complementary case in mind, note that the first person at your party can have their birthday on any calendar day, but after that, each person must have a different day. Let \(p_u\) be the probability that \(r\) people each have unique birthdays. We find \[p_u = 1 \cdot \frac{N-1}{N} \cdot \frac{N-2}{N} \cdots \frac{N-r+1}{N} = \frac{N!}{(N-r)!N^r}\] where \(N\) is the number of days in one year.

Backtracking to the original birthday problem, we now just need to find the minimum value of \(r\) people that satisfy: \[p_{s} = 1 - \frac{N!}{(N-r)!N^r} > \frac{1}{2}.\]

This expression doesn’t look all that pleasant to be solved outright, so instead we can build a little solver in Python--or the language of your choice!--to be able to compute \(p_s\) for any given \(r\) and \(N\).

def prob_birthday_success(r, N=365):

if r > N:

return 1.

factorial = reduce(lambda x, y: x*y, range(N-r+1, N+1))

power = N**r

return (1 - factorial/power)

We steadily increase \(r\) and once we hit the \(p_s \geq \frac{1}{2}\) mark, we have our desired party size. The table below illustrates solutions for 50% probability as well as a few others values of \(p_s\).

| Probability | People Required |

|---|---|

| 0.05 | 7 |

| 0.1 | 10 |

| 0.25 | 15 |

| 0.5 | 23 |

| 0.75 | 32 |

| 0.9 | 41 |

| 0.999 | 70 |

Notice that if we invite just 23 people to our party, we will have a 50-50 chance in finding a shared birthday. Inviting 60 or 70 people pretty much guarantees it. Incredible!

So it’s plain to see that \(p_s\) increases rapidly as our party gets bigger here on Earth, but this led me to consider: “What would happen if the party took place on, say, Mars or Jupiter?” Or in less whimsical terms: “How many people would we need if we varied the year length, \(N\)?”

Planetary Results

The first step in solving the birthday problem for the rest of our solar system is gathering year lengths for each planet, which vary wildly: from a meager 88 days on Mercury up to a whopping 60,182 days on Neptune. In fact, your entire life will be confined to a single orbital period of Neptune. There goes that Neptunian birthday party you’ve always wanted! (Admittedly, the definition of a “birthday” gets a little murky on these other planets… but more on this later.)

Once year lengths have been gathered, working out the problem for different values of \(N\) is as simple as returning to the Python function introduced earlier. The required number of party goers to achieve a 50% probability of birthday matching on each planet can be found below. As a child of the 80s, I must tell you it is VERY difficult for me to not include Pluto on this chart. But there’s always hope for a Plutonian comeback! 🙏

Even on Neptune where there are over 60,000 Earth days per year, we only require 290 people to have a 50% chance of matching birthdays. That’s an amazingly small amount for such a massive number of days in each year!

So now back to our broader question: “What’s the overall trend as \(N\) increases?” Well, the chart above is great for being able to read information associated with every planet, but it’s a bit misleading trendwise because both axes are on a log scale. Let’s take a look at this same information without the axial scaling.

Ah ha! Viewing the data this way, a trend that looks roughly like a power relationship emerges. We will now take a closer look at the analytic expression for \(p_s\) to dive deeper into this relation.

Expanding Solution with Approximations

We are about to embark upon the amazing world of expansions and approximations--AKA put your math pants on and fasten your seat belts! (If this sort of nerdout isn’t your thing, no worries. Just skip ahead to the end of this section where all will revealed… 🔮 Much of this work can also be found in Mosteller as his solution to the birthday problem.)

First recall that \[e^{-x} = 1 - x + \frac{x^2}{2!} - \frac{x^3}{3!}+ \cdots,\] so ultimately, \(e^{-x} \approx 1 - x\) for very small values of \(x\).

Now represent \(p_u\)--that’s the unsuccessful probability--as \[p_u = \frac{N(N-1)(N-2)\cdots(N-r+1)}{N^r} = \frac{N^r - \hat{k}}{N^r} = 1 - \frac{k}{N}\] where \(k\) contains multiple factors but all are smaller than \(N\).

Combining these two expressions, we then find that \[p_u = 1 - \frac{k}{N} \approx e^{-k/N},\] which is valid because \(k/N\) is typically much smaller than one.

Now let’s further consider the values contained within \(k\). Expanding out the numerator in \(p_u\), we have \[p_u=\frac{N(N-1)\cdots(N-r+1)}{N^r} = \frac{N^r - N^{r-1}\left[0+1+2+\cdots(r-1)\right] + \cdots}{N^r} = 1 - \frac{0 + 1 + 2 + \cdots (r-1)}{N} + \cdots.\] The quantity \(k\) represents several terms, but to leading order, it just looks a sum of the integers between 0 and \(r-1\). More specificially, \[k \approx 0 + 1 + 2 + \cdots + r-1 = \sum_{i=0}^{r-1}j = \frac{r(r-1)}{2}.\] So where does this lead us? Returning to our exponential expression above, we have \[p_u \approx e^{-k/N} \approx e^{-r(r-1)/2N},\] which looks much more tractable than the original expression we had for \(p_u\) containing those factorials. We can even come up with an expression to relate \(r\) to \(N\) more explicitly in the leading order.

Subbing in \(p_u = 1 - p_s\) and taking the natural log of each side, we eventually find \[\frac{r(r-1)}{2N} \approx -\ln{(1 - p_s)},\] which means \[r(r-1) \approx -2N\ln{(1-p_s)}.\] So there you have it! Selecting in any given value for \(p_s\) will fix the log factor and the other two quantities are related as \[\mathcal{O}\left(r\right) \sim \mathcal{O}\left(\sqrt{N}\right).\] The trend we saw in the planet chart was indeed a power relationship; specifically, \(r\) goes like \(\sqrt{N}\) as \(N\) increases for the birthday problem. This means that even on planets with many, many days in a year, we don’t really need to increase our party size by all that much to ensure our 50-50 chance of finding birthday twins.

Approximation in Action

How good is this approximation in practice? Well, the trendline we saw earlier in the true-scale axes chart was auto-fitted in Tableau with a power trend, and indeed, the equation for the resulting line was found to be

\[r = 1.28548 \cdot N^{0.491503}\]

So our square-root relationship appears to hold true.

We can also more explicitly consider what happens as \(N\) gets larger. Because we are estimating \[1-\frac{k}{N} \approx e^{-k/N},\] this approximation should actually become more valid as \(N\) becomes larger since \(k/N\) will resultingly grow smaller.

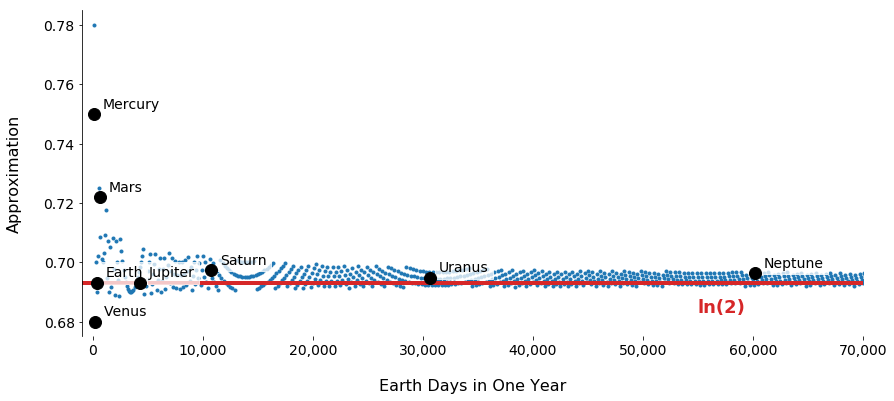

Now set \(p_s = \frac{1}{2}\) and let \(r_{1/2}\) be the 50-50 chance party size. Plotting the left-hand side of our approximation \[\frac{r_{1/2}(r_{1/2}-1)}{2N} \approx \ln{2}\] for various evenly sampled values of \(N\), we see in the figure below that this estimation indeed becomes more valid and encounters less variance about \(\ln{(2)}\) as \(N \to \infty\). (There is an added layer of complexity in this problem, however, because we require \(r_{1/2}\) to be an integer; this stipulation makes our approximation dance about the line a bit even at large values of \(N\).)

Conclusion

The birthday problem is a classic that has been examined from several different angles. I hope you’ve enjoyed this planetary rendition and the subsequent deep dive into analytic approximations to explore how \(r\) is related to year length.

A few final thoughts:

It is well-known that birthdays are not equally distributed throughout all 365 days, especially if you focus on one region of the world. So how does non-uniformity affect our birthday solution?

It turns out that the uniform distribution of birthdays we used throughout this post is actually a worst-case scenario in terms of successfully finding birthmates. If birthdays are skewed toward one day or another, the odds that you will find birthday twins at your party actually increase… but not significantly. Attempts at calculating the birthday problem with real-world datasets have shown the 23-person group to be a pretty consistent solution, even when considering non-uniform distributions.

I eluded to this earlier, but the idea of a “birthday” gets a bit complicated when thinking about other planets. I often mentioned my findings in terms of “Earth days” because I calculated each planet’s revolution about the Sun in the number of times it takes Earth to rotate about its own axis. What does that mean in the context of this problem?

Consider two cases: Jupiter and Mercury.

- Firstly, Jupiter rotates about its own axis in about 9 hours and 55 minutes, faster than any other planet in our solar system. So while Jupiter takes roughly 4,333 Earth days to complete its orbit about the Sun, this actually amounts to 10,476 Jovian days. That’s a lot more potential “birthdays!”

- Mercury, on the other hand, completes a rotation about its axis slower than any other planet. It takes about 176 Earth days for Mercury to rotate, which is longer than Mercury’s revolution about the Sun. Ultimately, a “year” on Mercury is half as long as a “day.” The birthday problem is completely moot because everyone born in the same Mercurian year is automatically born on the same Mercurian day! (… Please ignore the fact that no one is ever actually born on Mercury. 😆)

I have chosen to disregard this planetary difference in the definition of a “day” for simplicity, but keeping with the same Python function introduced near the beginning of this post, we could relatively easily compute revised birthday solutions. Please let me know if you work this out!

| Check out this code on GitHub! | Check out this viz on Tableau! |

MATHEMATICS · VISUALIZATIONS